The Impact of Your Brain on Adrenal Function

Our brain play an important part in our response to stress. Learn how brain affects the function of adrenal glands and contributes to the development of adrenal fatigue.

Most people have been taught that their adrenals are the source of their fatigue issues, and they naturally accept that line of thinking. In a sense, it is even true, since the hormones that so often sit at the center of our most common medical issues do originate from those glands. Even so, however, this “blame the adrenals” approach is perhaps too simplistic if we are to truly understand why our bodies react the way they do.

More importantly, that approach can prevent us from acknowledging and addressing the role of the other critical body part that impact this condition: the brain.

The Stress Response

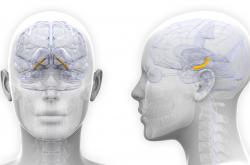

The body’s stress response – the way in which it responds to perceived threats and other outside stimuli – is actually governed by three distinct areas of the body:

- The hypothalamus, which is a tiny area of the brain that is responsible for controlling the release of hormones that influence eating, drinking, and sex - in other words, all of the things that make life worth living. It also regulates things like body temperature, blood oxygen levels, blood volume, and aspects of the sleep-wake cycle. Most importantly for your purposes, it is the area of the body that releases the corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) that initiates the sequence of events leading to the release of all those stress hormones.

- The pituitary gland, which serves as the transmitter through which the hypothalamus issues commands to the rest of the body. This is the gland that receives CRH from the hypothalamus. That hormone tells the pituitary to release adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), which then travel to the adrenals.

- The adrenal glands, which receive commands from the hypothalamus via the ACTH released by the pituitary. These are the glands that release hormones like cortisol and adrenalin to prepare the body to deal with whatever dangers the hypothalamus has detected.

Your Brain and the Center of Command

One of the worst things we can do as we try to learn to deal with stress is to fail to recognize it for what it is. It is easy to simply point at everything in our lives that we deem frustrating and call them “stress.” But are those situations and events really stress, or merely what they appear to be: situations and events?

After all, what frustrates you might seem perfectly harmless to me, and vice versa. Given that observation, the reality is that those situations and events that we tend to refer to as “stress” are nothing more than potential stressors – outside stimuli that may or may not incite our internal stress responses. In other words, it is not what is happening around us that causes stress, but our subconscious response to those factors that ultimately determines whether or not the stress response is activated.

That’s where the brain comes into play. It is the brain that works to identify and categorize an untold number of outside stimuli every moment of every day. Some of these people, events, and situations end up being classified as benign, and unworthy of a stress response. Others, however, get flagged by the brain as one form of threat or another, and your stress response is initiated to prepare you for whatever action might be necessary as you try to survive the perceived danger.

Good and Bad Stress Responses

The brain’s reaction to outside stimuli can be either positive or negative for you. If your brain receives sensory information that there is a horde of sword-wielding ninjas leaping out at you, the initiation of the stress response can save your life. The increased hormones will provide the muscle tension and energy you need to either engage them in combat or attempt to escape the danger by running away.

At the same time, that same stress response can spell trouble when your brain is registering minor annoyances as major stressors. If you find yourself becoming angered when the neighbor’s dog relieves himself in your front yard, then you can easily find your brain triggering the same type of stress response in reaction to you stepping in a pile of that dog’s daily delivery of delight. To the conscious mind, such a strong stress reaction makes little sense. After all, there is no need for a fight or flight response for such annoyances. But at a subconscious level, the brain often reacts to even minor stressors in precisely the same way it treats major threats.

Obviously, the brain has much greater influence over this process than most people assume. On both a conscious and subconscious level, this powerful organ controls the entire stress response. And while the old “I was just following orders” defense might not stand up in most courtrooms, in the case of the adrenal glands it would certainly seem appropriate.

It is the brain that identifies potential threats. It is the brain that categorizes those threats and assesses the actual level of danger and stress response that is warranted. And it is the brain that initiates and directs the pituitary and adrenal glands as that stress response plan is set into motion.

None of that suggests that the adrenals have no importance in the overall scheme of things, or that they cannot become overly stressed, damaged, and less able to function. Instead, it is recognition of the fact that the adrenals are not the sole culprit where exhaustion is concerned. The brain also has a powerful role to play in adrenal exhaustion, and it is typically the first cast member to make an appearance on the adrenal fatigue stage.

How the Brain Influences Adrenal Function

While the brain controls every aspect of adrenal activity, there are some specific areas of concern. These aspects of adrenal function are all governed by separate parts of the brain structure.

- The hypothalamus, as explained earlier, is the starting point for the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. It serves as the chief regulator of cortisol levels in your body.

- The mesencephalic midbrain is the part of the brain that determines the strength of the adrenal response.

- The pineal gland is responsible for maintaining the balance between melatonin and cortisol.

- This hippocampus works to ensure that cortisol follows the natural cortisol circadian rhythm.

Even a cursory examination of these four areas of adrenal response should make clear just how sensitive adrenal function can be to the slightest alterations in brain function. A little too much stimulation can cause the release of either too much or too little cortisol. Infections and certain diseases can prevent the hypothalamus from releasing the CRH needed to trigger cortisol production. Overreactions in the midbrain can result in an unnecessarily strong stress reaction to even minor stressors. And any disruption of the sleep-wake cycle can throw off the cortisol circadian rhythm and create an imbalance in hormonal levels.

The brain has a powerful influence on the body’s adrenal functions, but the regulatory systems that are in place to enable it to guide those functions are by no means foolproof. Even minor deviations in any part of the brain’s operations can result in misguided signals being sent to the rest of the body, and inappropriate adrenal responses to non-threatening situations and events. And when that happens over a sustained period of time, the effects on your health can be disastrous.

Gaining Perspective

There are, of course, those who have adopted a position that basically identifies the brain as the source of all adrenal-related difficulties. While there is an element of truth in that, it is also correct to say that the adrenals deserve some notice as well, since the adrenals do actually suffer dysregulation when their normal function is disrupted. A more balanced perspective would simply recognize that attention needs to be given to the brain and the adrenals if a successful recovery plan is to be adopted.

For while the adrenal glands may just be little more than factories that provide the hormones summoned into action by the brain, that does not make repairing them any less important for those who are trying to recover from adrenal fatigue. It just means that those patients shouldn’t think of their adrenals as the enemy – any more than they should resent their hormones, or even their brains. The descent into fatigue is a journey that involves many different systems and processes in the body, and the quest for full health must focus on each of these systems if it is to be successfully completed.

You might also be interested in:

- Adrenal Fatigue: Symptoms & Solutions For This Under-Reported Condition Even Your Doctor Doesn't Know. http://bodyecology.com/articles/adrenal_fatigue_symptoms.php

- The Brain and Adrenal Health. http://drbganimalpharm.blogspot.com/2010/04/brain-and-adrenal-health.html

- Treating Adrenal Burnout by Changing Your Brain. http://www.nancydeville.com/blog/2010/04/treating-adrenal-burnout-by-changing-your-brain/

- Brain Gut 16: Adrenal Fatigue Rx. http://www.jackkruse.com/brain-gut-16-adrenal-fatigue-rx/

- Your stress response: the details. http://www.youramazingbrain.org/brainchanges/stressbrain2.htm

.jpg)

Leave a comment